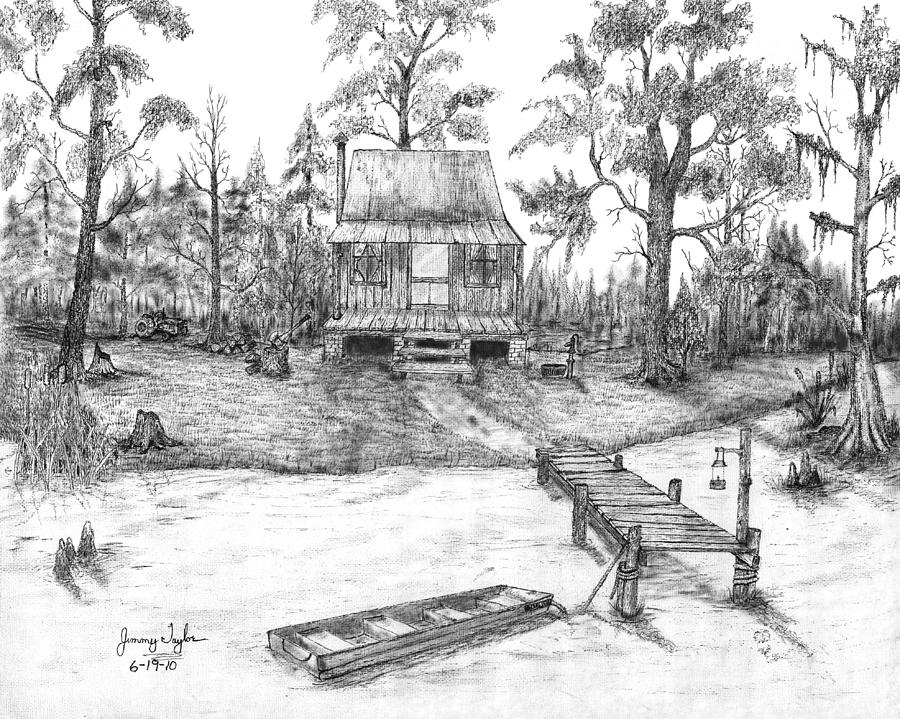

Peter Damian Bellis’s novel, set in the deep bigoted South of revival meetings, alligator hunts, Spanish moss and bible bashing lynch mobs occupies a similar fictional territory to Faulkner and Peter Mathiessen’s Shadow Country. It consists of two intertwined and alternating narratives, that of Thaddeus, a man of no origin, an outcast, a loner who is his own sort of conjure man, who comes to live on the edge of a small community; and a boy who forms an uneasy friendship or alliance with him. The connections between these two characters is teased out over the course of the novel until gradually their relationship becomes clear to the reader. Interleaved with these two narratives is a third narrative describing the vanquishing of a (possibly mythic) alligator by a huntsman: this fable illustrates themes of ‘nature red in tooth and claw’ in which man establishes primacy over nature through cunning and cruelty.

Bellis is a marvelous, sure-footed stylist, employing a breathtaking range of totally different styles and voices for the two main narratives. The first person voice for the boy reproduces with marvelous accuracy the rhythms of Southern rural dialect, the kind of ungrammatical word-salad the woefully undereducated produce (this voice is highly infectious, and I found myself ‘speaking’ it for several days while reading the novel). Bellis achieves here a kind of beauty and sincerity which seems to elude most contemporary American novelists who ‘do the police in different voices’ and who usually only achieve pastiche.

Time we up to the square, the festival lights they already on. The parade it done with and most the folks they done circle back to the tables. I aint see Mama or either Tramsee for too many folks, but there Willie in front of the barbecue, and he smoke-shouting for everybody step on up and get some…

The third person voice for Thaddeus is quite different although recognizably from the same locale, modernistic, stream of consciousness, in turn split between two voices, that of the narrator and that of the internal monologue of Thaddeus’s memory, this voice tumbling on unbroken by sentence boundaries:

…the good Reverend now forgotten, him in his black church boots standing once more in front of the now smoke black tent beneath the quaking aspen, the Reverend watching the tent burn to the ground, the bible still in his hand, a dream of what was to come, perhaps, or what was, or what might have been, or so it seemed…

The novel is hugely atmospheric: one can feel the mosquitos biting and the crabs tugging, and there is an almost unbearable sense of menace and threat hanging over everything, occasionally erupting into shocking scenes of violence which seem to arise out of the landscape itself. Bellis is himself a conjure man, able to bring to our eyes and senses a very realistic depiction of a specific milieu.

The novel contains a number of brilliant set-pieces, one of which is extracted in the excellent short story collection: One Last Dance with Lawrence Welk, in which this writer’s ability to conjure up a range of settings, voices and characters is also displayed to the full.

Quentin Brand, June 2018, The Lectern